Refrigerant management is the most impactful step to solve the climate crisis, as many people on our staff were surprised to learn when we featured Paul Hawken’s new book Drawdown in our winter issue.

We thought the top solution would be something environmentalists talked about more—like increasing wind and solar power or protecting forests. Even Hawken admitted that refrigeration management was “less sexy” than what he’d hoped would top the list.

But after reading Drawdown, I had to know more about the book and nonprofit’s number-one climate solution. Instead of focusing on the need to phase out harmful refrigerants, I wanted to see how systems currently in development could help the world reach goals to reverse climate change.

The Problem of Refrigerants

The major issue with refrigeration (including both refrigerators and air conditioning) is the ozone-harming chemicals and greenhouse-gas chemicals that it releases into the air.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol, an international, legally binding agreement, phased out two types of harmful refrigerants in wide use prior to that year: chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs), which were responsible for tearing a hole in the ozone layer.

Though they helped repair that hole, the replacement chemicals, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), are 1,000 to 9,000 times more potent than CO2 in terms of their climate impact, and they are still in prominent use today.

Under the Clean Air Act, it’s illegal to “cut the line” and release potent refrigerants into the air. But that’s almost impossible to enforce when thousands of fridges arrive at landfills across the country every day. Eventually, 99 percent of refrigerant chemicals make it into the atmosphere.

Electricity is also a problem of refrigeration appliances. Unlike a washing machine, another high-energy appliance, people run their refrigerators 24/7, and as the world warms, more and more people rely on air conditioning to keep spaces bearable.

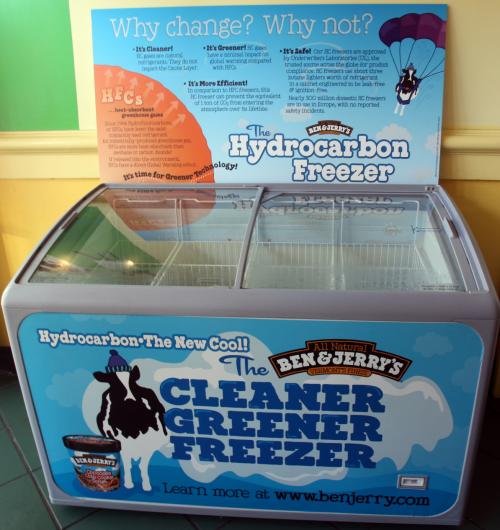

Ben and Jerry’s reduced its climate impact by bringing the first hydrocarbon freezers to the US in 2008. These freezers have a much smaller climate impact than conventional freezers. Photo courtesy of Ben & Jerry's.

Green Coolants of the Future

New technologies for refrigeration have huge potential to help reverse the climate crisis.

Under the 2016 Kigali amendment to the Montreal Protocol, nations began to phase out HFCs. Subsequently, the chemical industry began to market hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) as an Earth-friendly alternative to other gases, but they, too have harmful effects, says Janos Maté, a senior policy advisor at Greenpeace.

“When HFOs decompose in the atmosphere, they form trifluoroacetic acid, which is a toxin that accumulates in wetlands. This could bring about yet another global ecological disaster,” he says.

Scientists are working on better alternatives. Magnetocaloric coolers are based on the thermodynamic effect, which shows that “the temperature of a material can be changed by exposing it to a magnetic field,” explained journalist Michael Irving in New Atlas. These fridges cool by exposing an alloy to a magnetic field—certain alloys will heat up or cool down when this happens. Then, they pump low-impact liquids around the alloy, which cools the liquid so it can cool the fridge interior.

But a different kind of cleaner refrigerator is already on the market. In the 1990s, the advocacy nonprofit Greenpeace invented GreenFreeze as a climate-friendly solution.

GreenFreeze uses naturally occurring hydrocarbons, mainly isobutene as the refrigerant and cyclopentane as the insulation foam-blowing agent, or the foam that insulates the doors and walls of fridges. These efficient refrigerants are thousands of times less potent as global-warming agents than fluorocarbons and don’t break down into acid like fluorolefins.

Nearly a billion GreenFreeze fridges are in use globally, says Greenpeace’s Maté.

“Hydrocarbons, along with the other natural refrigerants, are also used in commercial applications, such as vending machines, ice cream freezers, point of sale equipment, supermarket refrigeration, and room and building air-conditioning,” he says.

Despite that, they’re not yet widely available in the US, where the chemical industry used its powerful influence to stop the EPA from approving natural refrigerants for sale.

Despite the setback, Ben & Jerry’s brought the first hydrocarbon freezer stateside in 2008, which the EPA allowed on a trial basis. In 2011, the EPA officially allowed manufacturers to sell natural refrigerants in the US.

Maté says that today, natural refrigerants can fulfill most of our cooling needs, and with economies of scale making prices competitive with conventional refrigerators, they could fulfill all of them.

In 2010, the UN’s Technology and Economic Assessment Panel projected that by 2020 at least 75 to 80 percent of global new refrigerator production will use hydrocarbon refrigerants.

Better Refrigerant Recycling

According to Drawdown, 90 percent of the emissions of refrigerant chemicals happen during disposal. From 2007 to 2016, Americans discarded an estimated 175 million refrigerant-containing appliances, including fridges, freezers, dehumidifiers, and air conditioners, according to the EPA’s Responsible Appliance Disposal (RAD) program.

Through partnerships with utilities, retailers, and states, RAD sends fridges to certified recyclers for proper disposal of refrigerants and foam-blowing agents and recovery of other materials.

Only about four percent of the discarded refrigeration appliances made it to RAD recyclers in that decade, and while others may have been recycled or sold on secondary markets, millions end up in landfills, where the focus tends to be more on reselling metals and less on proper disposal of harmful materials, though it is federal law that ozone-depleting substances and other harmful materials be disposed of properly.

Since 2007, RAD partners have recycled over 7 million refrigerators and freezers and nearly 52,000 air conditioning units, according to the program. Its greenhouse gas reduction is the equivalent of keeping 6.7 million cars off the road for a year.

Though refrigeration recycling is gradually catching on, the future of EPA programs is unclear with Scott Pruitt at the helm. Advocates consider Pruitt to be a threat to clean-energy programs but not necessarily recycling ones.

Learn how to recycle your old fridge, air conditioner, or humidifier through RAD.

Smart Fridges Save Energy

Over time, using less electricity for refrigeration can have a big impact on climate. Smart fridges could help with that. Companies that make smart fridges promise these appliances will make our lives better, but for years, customers have scoffed at this manner of introducing one more screen into their homes. Less than two percent of fridges sold in 2016 were smart fridges, according to Statista.

Dan Saffer scoffs right back at the critics. He’s a senior product designer for Twitter (meaning he works on the design of the social media platform itself), and he’s an expert on interaction design and user experience. Saffer says it’s not about the screen. It’s about refrigerators that can be more useful than they are now—and save people money.

“The refrigerator is one of the biggest draws on electricity, so this thing will pay for itself, especially because the lifespan of refrigerators is 10 to 15 years,” he says.

A smart fridge can learn your fridge-opening habits and cool at times that would be most efficient.

These fridges can also use something called demand response to talk to local utilities to optimize its internal processes. Utilities give better prices for electricity used at off-peak hours. Through demand response, your smart refrigerator’s computer will, for example, put off heating the coils (which keeps them from freezing) for a few minutes or hours so this energy-intensive function happens off-peak.

According to a 2013 report from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, demand response implemented in refrigerators could save consumers $2 to $4 a month on their electricity bills.

This might not be enough to make the cost of buying the smart fridge worth it for a homeowner, but for a facility like a grocery store with dozens or hundreds of refrigerators, this could be game-changing.

Demand response is already in place in many industrial settings. When Great Lakes Cold Storage’s instituted demand response in its refrigerated warehouse in Cranberry Township, PA, it saved nine percent on its electricity bill in the first month, and, over two years, lowered the bill by 58 percent.

Homeowners who are concerned about the effects of wireless devices on human health (see p. 18) may want to skip this feature. Right now, most smart fridge brands have not yet incorporated demand response, while customers can turn it on in WiFi-connected Samsung and LG fridges.

Looking to the Future

As outlined in Drawdown, a change in refrigerant management could save the world 89.74 gigatons of reduced CO2 equivalent by 2050, the single top solution for stopping global warming.

From changing how our old appliances are recycled to how new ones will be made, options are already in place for reducing the impact of refrigeration.

This is a shift that for many can start at home when it’s time to replace an appliance. To make the biggest difference, farmers, grocers, and anyone working with refrigeration commercially must prioritize climate.

What you can do

- Maximize the efficiency of the fridge or freezer you have by keeping the coils clean and filling empty space in the freezer with jugs of water.

- If you need a new fridge, buy one that uses GreenFreeze/hydrocarbon technology.

- Tell your supermarket and other stores to switch to climate-friendly cooling appliances.

- Responsibly recycle your old refrigerator and AC unit with the RAD program.

- Ask your representatives in Congress to mandate the early phase-out of HFCs where alternatives are available.